From an early age, Loyola professor Matt Bodett knew he would be an artist, even skipping high school classes just to draw all day.

Art was his escape then. It later would become his salvation when a mental disorder led to a breakdown that turned his world inside out and had him questioning his very existence.

As a side effect of a five-year medication trial, Bodett said he “would gnaw on my own tongue and it was just miserable. Or [I would] be a vegetable, just checked out, and there was a lot of joylessness.”

Eventually, thanks to persistence and a strong support system, he was able to climb out of the abyss. But for every Matt Bodett in the world, there are thousands of others who never detach themselves from the grip of a mental disorder, as a result of either a lack of access to resources or because they never find the light that will lead them out of the darkness.

Michen Dewey

Michen DeweyMatt Bodett teaches and makes art, but also spends time as a mental health advocate.

“Most people diagnosed end up on government support for the rest of their life because they can’t hold jobs and can’t function well in society. At least that’s what we’re told, that you might be homeless, you might be in a hospital for the rest of your life,” Bodett said.

Even if these individuals are provided with housing, it’s not likely that they’ll continue to have residential stability unless they have access to continued treatment and services, according to the National Mental Health Association.

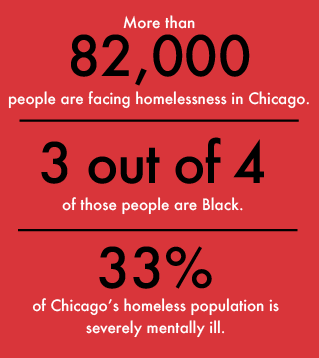

In the United States, one-third of the homeless population suffers from some form of untreated mental illness, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). Chicago ranks higher, with 33 percent of the city’s homeless population afflicted, according to the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless.

Bodett was more fortunate than many when his disorder began to take over his life. As he started college in 2002 at Ricks College, now named Brigham Young University – Idaho, he felt the pressure many art students face when thinking about if being an artist is going to pay the bills. He decided to major in art education, thinking being paid to teach about art would be a happy medium. But after a few years of undergraduate work, all of that changed.

In 2004, at the age of 22, Bodett was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, which is not to be confused with schizophrenia. The difference being the former has symptoms of both schizophrenia and either depression or bipolar disorder, and affects 0.3 percent of the population, according to NAMI. Symptoms include hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thinking, depressed mood and manic behavior.

At this point, Bodett had been in college for a few years, and realized after the diagnosis working with kids might not be an option.

“My view of schizophrenia before I was diagnosed, or even after I was diagnosed, was really bleak, and I did not have a lot of hope for what was going to happen. So, I figured if I’m going to be unemployable for the rest of my life, I may as well make art,” Bodett said.

Prior to his diagnosis, Bodett said he often experienced hallucinations and paranoia.

“One day I was inputting data onto a computer, and I felt like I was in this weird vortex where time is moving really slow [and the] room was starting to change its structure around me,” Bodett said. “It was a really off-putting experience, and I couldn’t figure out what was happening.”

Bodett went to the campus counseling center, where he was seen by a professional who started him on medication after diagnosing him with a bipolar disorder, a common misdiagnosis for people with schizoaffective disorder, according to NAMI. By the end of the summer, Bodett said his doctors took him off the medication, causing him to have a major breakdown and be hospitalized for treatment.

Bodett had to move back home to live with his parents and transfer to Boise State University, which turned out to be a blessing. Due to Bodett being on Medicaid at this point, he had social workers and a psychosocial rehab worker — a person who would come to his house every day and get him to go for a walk, shower and brush his teeth.

For a brief time, Bodett’s parents wanted to keep his situation private, even from family members. But they ended up taking classes through NAMI, the nation’s largest grassroots mental health organization. NAMI supports individuals and families affected by mental illness, aims to reduce stigma and advocates on a political level for the rights of individuals with mental illness, according to Kasey Franco, NAMI Chicago’s training and outreach coordinator.

Bodett’s parents went through a free 12-week program offered by NAMI called Family 2 Family, during which topics such as diagnosis, crisis, rehabilitation, relapse and medication are discussed in a support group setting.

“What we try to do is allow them to gain some empathy by understanding what a person with mental illness experiences through a variety of exercises … and of course [discuss] self-care for the caregiver coping with worry, stress and being overwhelmed,” Franco said.

For his part, Bodett initially had to work with new doctors and try different medications. “It was a series of four or five years of just miserable medications,” said Bodett, who discovered that he couldn’t create the artwork he wanted to while on the drugs.

“I couldn’t pursue the things I needed. I could hardly draw, and [that] was the thing I loved and it hurt too much to not have that in my life,” Bodett said.

Over time, he learned to cope with his symptoms without medication, relying instead on meditation through art. He said in no way is he against medication, and in many ways it can be life-saving. It just didn’t work for his specific situation.

“It was an opportunity to use art to understand my situation, because nobody else that I knew could tell me about it. There’s no way for me to seek help for what I was going through other than my counselors. And I can’t tell them everything because I don’t have words for everything.”

Bodett discovered creating art had become a way of learning to listen to his body and recognize the stages in which his illness presents itself: first with anxiety, followed by paranoia, which turns into isolation and, finally, hallucinations.

Today, Bodett has come full circle with his original college education plan, having taught at Boise State University, College of Western Idaho, College of Idaho and Loyola, where he teaches drawing.

Bodett also is a mental health advocate, through a series of performance art and by serving on the advisory council for the Institute for Therapy through the Arts (ITA). ITA is a community-based arts program that treats children, adults and families, according to Marni Rosen, ITA’s practice director.

The ITA advisory council is made up of colleagues and members of the community who have experiences ITA can benefit from, according to Rosen. She said the council is assembled as a way to gather information outside of the resources ITA already has to give different perspectives, new ideas, connections and enrich the program.

Rosen said Bodett is just one of a council of people who come from different backgrounds and experiences. She said ITA appreciates Bodett’s support and “highly respects his advocacy work.”

Bodett’s performances are a set of 12 productions that relate to different aspects of mental health, such as identity, suffering, healing and stigma. One of the groups sponsoring his performances, 3Arts, is an organization that focuses on supporting women artists, artists of color, and artists with disabilities through promotion, residencies, project support and cash grants, according to 3Arts’ Director of Programs, Sara Slawnik.

Slawnik said she attended one of Bodett’s audio-visual performances, describing it as ground-breaking, and hopes more people learn from his shows.

“It was an incredible performance using accessibility services to ensure people with vision impairments are able to experience the work. Matt had a really amazing collaboration with the audio describers and [Steppenwolf] Theater to make it a really special and creative performance,” Slawnik said.

In the midst of a breakdown and medication trials that didn’t work, all could have been lost for Bodett if it weren’t for art and a lifeline of support. Through this experience, he said he has learned the most important things about getting better are being willing to talk to someone, listening to those who want to help you and seeking counseling services.