The house is getting noisier on a Monday afternoon. The kids have come home hungry from school. Snacks are handed out. In a few minutes, everyone will come together to talk about their day before they start preparing for dinner.

After dinner, the kids will do their chores and once again meet in groups, discussing current events, career planning and mental health. Then they will have some free time to call family members, clean their rooms or complete homework before lights go out at 10 p.m.

At 5:30 the next morning, the kids will do it all over again—unless they have a court date.

In that case, the staff at the Manuel Saura Center in Chicago’s Logan Square neighborhood, where the kids reside, will take them to their court appointment.

The center is a residential program that acts as an alternative to juvenile detention, allowing youth to have a secure and stable place to stay for up to 30 days.

The Saura Center and similar programs aim to keep youth away from the common stereotypes within the justice system, like institutionalization and repeat offenders, as well as the negative effects of detention centers on children’s mental health, education and overall development.

Stephanie Boho-Rodriguez, the Director of the Juvenile Detention Alternative Initiative Programing in Chicago, has been with the Saura Center since it opened almost 21 years ago.

“We started in 1995 as a pilot program,” Boho-Rodriguez said. “The Cook County juvenile courts were looking for some alternative programing to secure detention, so they partnered with the Annie E. Casey Foundation and started the Juvenile Detention Alternative Initiatives.”

Amanda McDonald

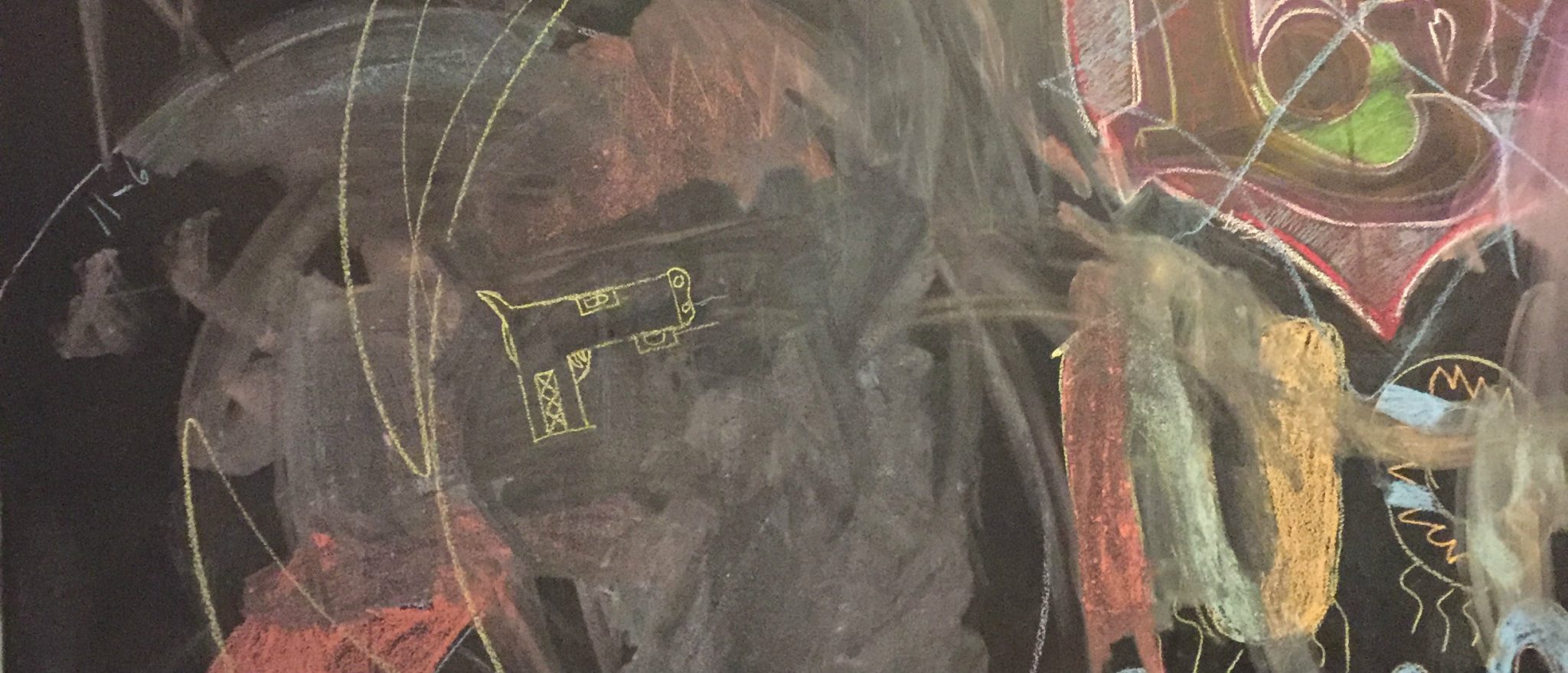

Amanda McDonaldA mural was painted in the basement of the Manuel Saura Center in Logan Square by participants within the alternative youth program. It represents going from the dark to the light.

Other similar youth programs in Chicago include home confinement, day or evening treatment, group homes and specialized foster care, according to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency in a 2014 study.

Substitutes to secure detention “were developed in response to research indicating that detention and confinement may do more harm than good” for children, according to the study.

“We are considered to be the most restrictive because the kids actually get court ordered to live here in a residential setting,” Boho-Rodriguez said.

The number of juvenile arrests in Chicago in 2013 approached 21,500. While that number decreased in 2014 to just over 17,700, 19.1 percent of the arrests in those years resulted in the juvenile going to a detention center, according to a report published by the Illinois Juvenile Justice Commission, an advisory group dedicated to safeguarding juvenile justice.

The Saura Center receives referral participants directly from the court system or from police departments within the county and can house up to 36 kids at once. The participants range from ages 10 to 17, can be male or female and must have a pending case. Youth with histories of arson, overt sexual behaviors or homicidal or suicidal tendencies are not accepted into the program.

Most participants are assessed as to whether they need to be in secure custody following their arrest. From there, they are either sent home or referred to the center. Referrals can come in 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Once the child arrives at the four-story Logan Square location, he or she goes through an orientation and is assigned a case manager.

Day-to-day activities include craft and cooking groups, chores, and on the weekends, outside activities for those who held a 90 percent success rating in their weekly point and level system. Participants start each day with 100 points and can lose them based on various offenses such as cursing (five points), verbal abuse to other participants (11 points) or verbal abuse to staff (16 points).

Those who kept their point total above 90 each day are awarded by moving up a level. Certain levels are allowed to travel with the group to see movies, go bowling or to exercise at Planet Fitness, which offers free services to the center.

While their schedule is extremely structured, consistency is key, according to several participants whose names have been changed to protect their privacy.

“This was a blessing,” David said. “[Juvenile Detention] wasn’t for me. Here, I do chores.”

Another male participant, John, also complimented the structure of each day.

“They give everybody a job,” he said.

Matthew commented on being able to connect with the other participants due to their similar circumstances.

“I know everybody in here likes basketball, sports and girls,” he said. “[It’s] a place where I get to come and think.”

- The center features an art gallery.

- Participants are required to keep their bunkbeds clean.

The increased violence in Chicago has affected the Manuel Saura Center. Homicides have risen in the city by nearly 55 percent compared to 2015. The number of children who come in with gun related charges has gone up, Boho-Rodriguez said. Those include unlawful weapons charges, strong-armed robbery and vehicular hijacking with a weapon.

Despite the rise in violent gun offenses, Case Manager Jennifer Lucatero sees the positive effect of the program every day when she comes to work.

“None of them want to be here, but they’re lucky to be here,” Lucatero said. “It’s cool because they come in with a defense mechanism, but you see them act their age again.”

The success rate of alternative programming is promising. Those who participated in alternative treatment programs were significantly less likely to enter into the justice system within a year of completing their program. In addition, boys in alternative programming were seen to have a “larger reduction in official criminal referral rates, [and] fewer self-reported criminal activities” than others, according to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention study.

For Boho-Rodriguez, Lucatero and the other staff members, having a participant leave the program “successful,” or leave without getting a violation is the most rewarding feeling. Instilling the mantra that these kids can do something positive with their lives is the ultimate goal.

“We have to make them wander outside of the street life…[and] let them know that there’s a life outside of gangs,” Lucatero said. “When they get slapped with labels their whole lives they start to believe them.”

The participants see the work the staff does, and many are appreciative.

“They deal with kids with attitude… They take time out of their day to take care of kids they didn’t bring into this world,” Daivd, a high school senior, said.

Once he leaves the program, he does not want to come back. This is not in a negative sense, but because he wants to go to college. Through clinical and focus groups dedicated to education and college, he learned he has options besides returning into the justice system.

“Once I leave here,” he said, “I want to start my own businesses.”