Candace Moore is optimistic about the drop in suspension and expulsion rates in Chicago Public Schools, but worries that the city may be straying away from confronting the deeper issue.

Moore is a staff attorney at the Chicago Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law where she helps protect the educational rights for kids across the city by providing direct representation for students facing expulsion to policy work. She is passionate about eliminating CPS’s zero tolerance policy, which includes tough disciplinary practices that were in place until a few years ago.

The policy reflected a national trend that began in the 1990s starting with the Clinton crime bill, said Jon Schmidt, clinical assistant professor of education at Loyola University Chicago.

The thought, Schmidt said, was, “If we really clamp down on disciplinary behavior and rid it out immediately, that would be the solution…[but] it hasn’t really worked out that way.”

The Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning has found that suspensions, which were very popular under the zero tolerance agenda, have been shown to actually lower achievement while also leading to higher drop-out and incarceration rates.

“Restorative justice was really available all the way back to the 1990s,” Schmidt said. However, it has historically been presented as an option for schools, not a requirement.

Schmidt said the turning point was in 2014: “[CPS Superintendent] Barbara Byrd Bennett delivered a press conference and said we are suspending and expelling far too many students of color.” Now, they have become “the norm and expectation.”

“CPS doesn’t have a ‘zero tolerance policy’—far from it. We emphasize restorative justice,” said CPS communications director Emily Bittner.

The restorative justice practices Bittner is referring to include partnering with outside groups and taking time to check in with students throughout the school day. To some extent, these practices have been successful.

On Sept. 22, 2016, CPS announced that expulsion and both in- and out-of-school suspensions reached an all-time low. According to CPS, out-of-school suspensions decreased by 67 percent while expulsions decreased by 74 percent since 2012, when the disciplinary shift began.

A University of Chicago study found that during the 2009-10 school year, approximately 25 percent of high school students received at least one out-of-school suspension each year. By the 2013-14 school year, that rate dropped to 16 percent.

“It is a good thing that suspensions and expulsions have dropped tremendously,” said Moore. “When you have exclusionary discipline as the rule, you create a situation where many students just aren’t even getting a second chance to come back and learn from those mistakes.”

Now the school district has created an Office of Social and Emotional Learning, which partners with CASEL, to spearhead the change in disciplinary practices.

In a punitive disciplinary system, CASEL explained, misbehavior is seen as “breaking rules” and “disobeying authority,” whereas in a system focused on restorative justice, misbehavior is “harm done to one person/group by another.”

Another key difference between punitive and restorative practices is what the focus is on. CASEL believes a punitive system focuses on “establishing what rules are broken and who’s to blame,” while a restorative system focuses on “problem solving, relationship-building and achieving a mutually-desired outcome.”

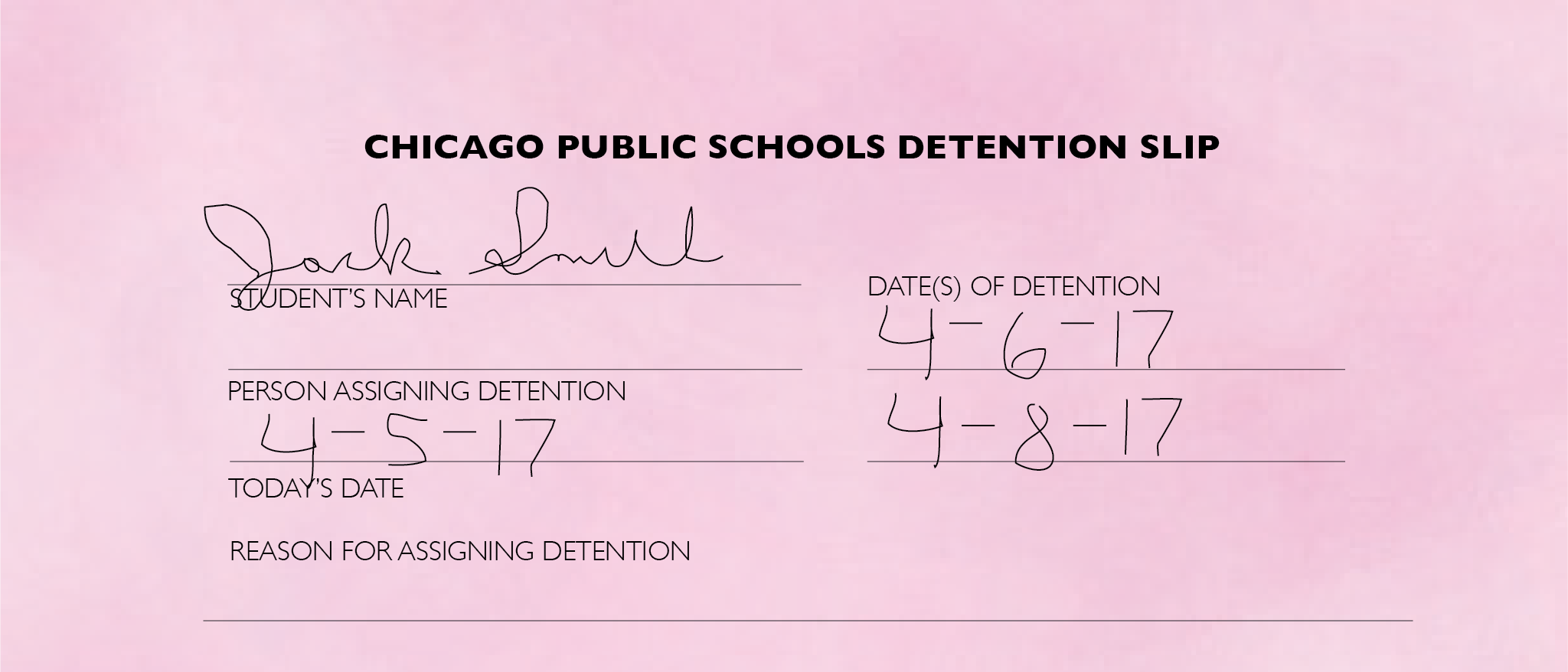

A key change in policy that’s taken place during this transition is state bill SB0100. This bill, sponsored Sen. Kimberly Lightford (D-Westchester) and Rep. Will Davis (D-Hazel Crest), makes changes across the state, most notably limiting the maximum length of a suspension to three days unless the student poses a threat. It has been in effect since Sept. 15, 2016.

At its foundation, the bill aims to make exclusionary discipline policies, such as suspension and expulsion, a last resort. It is one of many bills which have made changes regarding a suspended student’s re-integration into the classroom.

Previously, a student could be suspended and miss up to two weeks of class and schools were not required to help these students make up missed work. Because of SB0100, students are given that chance.

Antonio Magitt, 18, is a senior at Roosevelt High School who was regularly disciplined at school until recently. He has attended five schools, mostly due to expulsions.

“It’s good that we have a bill like SB0100,” Magitt said.

He feels that the bill would have benefited him if it were implemented earlier. While at Roosevelt, Magitt said he was suspended for two weeks after a verbal argument with a guidance counselor who he felt was mistreating him.

“I shouldn’t have stayed out of class for two weeks,” he said. “I ended up failing so many classes for that.”

Moore said this bill is important “because it’s the first time the state has done legislation that’s really highly focused on the student-to-prison pipeline.”

“Every school in the state is going to be playing by the same rules,” she added, which is a significant change, especially for students that attend charter schools.

Right now, the implementation phase of the bill is underway.

“It’s great that we have new laws on the books,” said Moore, “but it only matters if people follow them.”

An issue that both Moore and Schmidt agree on is that CPS needs to work on enabling teachers to be prepared to handle disciplinary situations in the classroom.

“Teachers are now being encouraged, in some ways mandated, to keep kids in the classroom where a year ago, two years ago, they could say that’s it, you’ve got to go,” Schmidt said.

“As a teacher, I feel like my hands are tied because before I would remove them from the school, but now I can’t do that,” Moore said. She explained that for the most part, teachers aren’t given another way of dealing with behavioral problems.

Outside organizations are beginning to give CPS teachers the training to deal with these types of situations, which has not been a requirement in the past, Schmidt said.

Although restorative justice practices have resulted in decreased suspension and expulsion rates, Moore thinks Chicago should be investing its money in “counseling, social work, [and] mental health”—things that are known to work but have been avoided because they require financial resources, which have been hard to find with the continuous budget cuts.

While restorative justice initiatives have shown measurable improvements, they can only do so much.

“Students were having undesirable behaviors because of something,” Moore said. “To me, the stats around the lowering of the rates is good and I applaud CPS for taking that step, but on the flipside of it is the challenge of: did we actually serve our children or did we just change our policy around it and our children are still hurting?”

The most important question remains: “Are these students really being helped?”