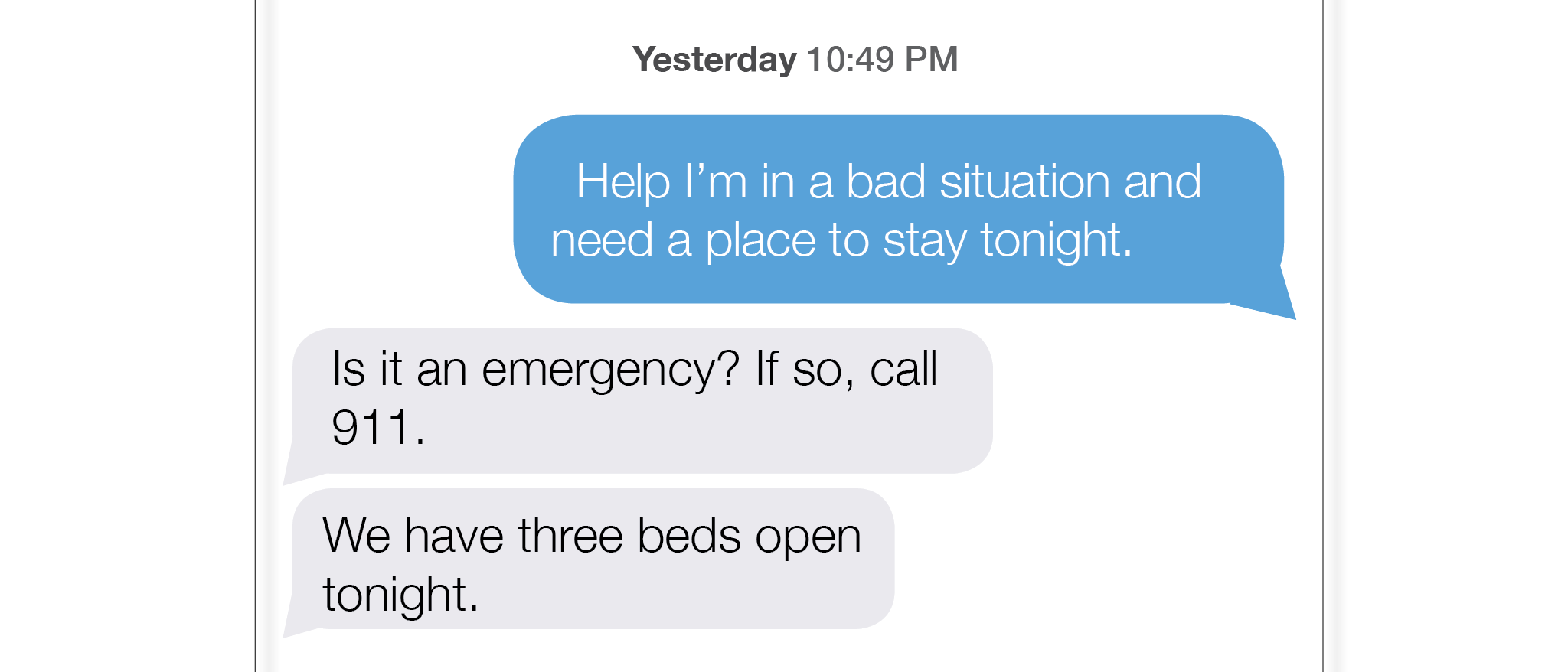

Tiffiani Turner drives up from the South Side of Chicago every day to work her 7 a.m. shift at the Domestic Violence Hotline. She arrives at the office and begins the routine of logging into the care network, checking emails and the 24-hour texting service.

One day, after connecting her phone line, she checked the most necessary resource: the number of available beds in emergency shelters for domestic violence victims.

On that particular day, of the 142 beds in Chicago for domestic violence victims, there were two beds available. Two beds to service the 2.7 million people living in the City of Chicago. The phone rang.

“All of us operators are empathic. Most of us understand from experience that it is not an easy choice, we are listening to people. They call not because they want a fix, they call because they want someone to hear them,” Turner explained.

She has answered phones at the Hotline for 17 years and has a personal understanding of domestic violence victims—as a child, she witnessed her mother’s abuse.

Protection for victims has grown as issues like gender equality and feminism become more commonplace. The passing of legislation, like the 1984 Victims of Crime Act, increased funding for victim focused welfare. This funding comes from fines levied on domestic violence offenders that is then sourced to victim orientated services and compensation. Yet, the occurrence of domestic violence remains high with one in four women domestically assaulted within their lifetime.

“Data in many ways has been informing the work in domestic violence counseling and policy for the past 40 years,” Reshma Desai, a strategic Policy Specialist with Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, said.

The Domestic Violence Hotline receives on average over 2,000 calls a month. The 14-person organization provides callers with information about legal services, safety action plans and emergency housing. Founded in 1998, the hotline expanded in 2007 to receive calls from across the state of Illinois through city, state and federal funding.

The modern definition of domestic abuse includes psychological, emotional, financial, sexual and the most visible, physical abuse. This growth in definition is sometimes difficult for victims to comprehend. Victims programs like the Domestic Violence Hotline have the balancing act of being informative about abuse, as well as supportive about realistic options.

Often through the preliminary questions asked by operators, victims will reveal other forms of abuse, such as issues with sexual consent. When consent is not given or sexual contact occurs because of fear, it is considered sexual domestic abuse.

Since many victims struggle with separating from the abuser, mental barriers are put up. The first barrier is an emotional one, as victims are often abused by intimate partners. History, memories, and emotions tie them together and the reality of losing their partner is outweighed by the abuse. Leaving their abusers could isolate victims from family and cultural bonds even further.

“It takes an average of seven attempts for a woman to leave her abuser,” Desai said.

Before her work at the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, Desai was the director of Rainbow House, the largest emergency shelter for domestic victims in Chicago. The shelter, which has since closed, received calls from the Domestic Violence Hotline when victims needed emergency housing.

The second barrier victims face when leaving is a logistic one.

“Two of the biggest issues are employment and housing. Victims can’t leave because they don’t have a place to go, and there isn’t affordable housing. If they don’t have a job they can’t get rental assistance,” Qwyn Kaitis, Director of the Illinois Domestic Hotline, said. “Even if people want to leave they can’t. Financially they can’t, there is a limited amount of shelter space… thousands of victims would leave if they could.”

This balance of giving the victim power and information while not condoning the abuse is the priority of operators as they help domestic violence victims in Chicago. It becomes even more of a challenge when resources like shelters are unable to handle the amount of victims. This is the biggest challenge facing operators like Turner.

“What are the goals we want? We don’t want to set victims up for failure. The victim has final say,” she said.

Turner’s coworker hangs up the phone, those two beds have been filled by a mother and child. 142 people are safe from their domestic abusers, but thousands will have to explore other options to stay safe.