Latonya Maley creates a striking figure as she strides through the halls of the Broadway Youth Center. In a tea-length ’50s style pink dress with black polka dots, wedge heels, and dreadlocks that fall over the tattoos on her dark-skinned shoulders, the 28-year-old self-identified lesbian radiates confidence, femininity, and strength.

Maley is the director of the Broadway Youth Center, a branch of the LGBTQ service provider Howard Brown Health in Lakeview, Chicago, that caters specifically to youth ages 12 to 24.

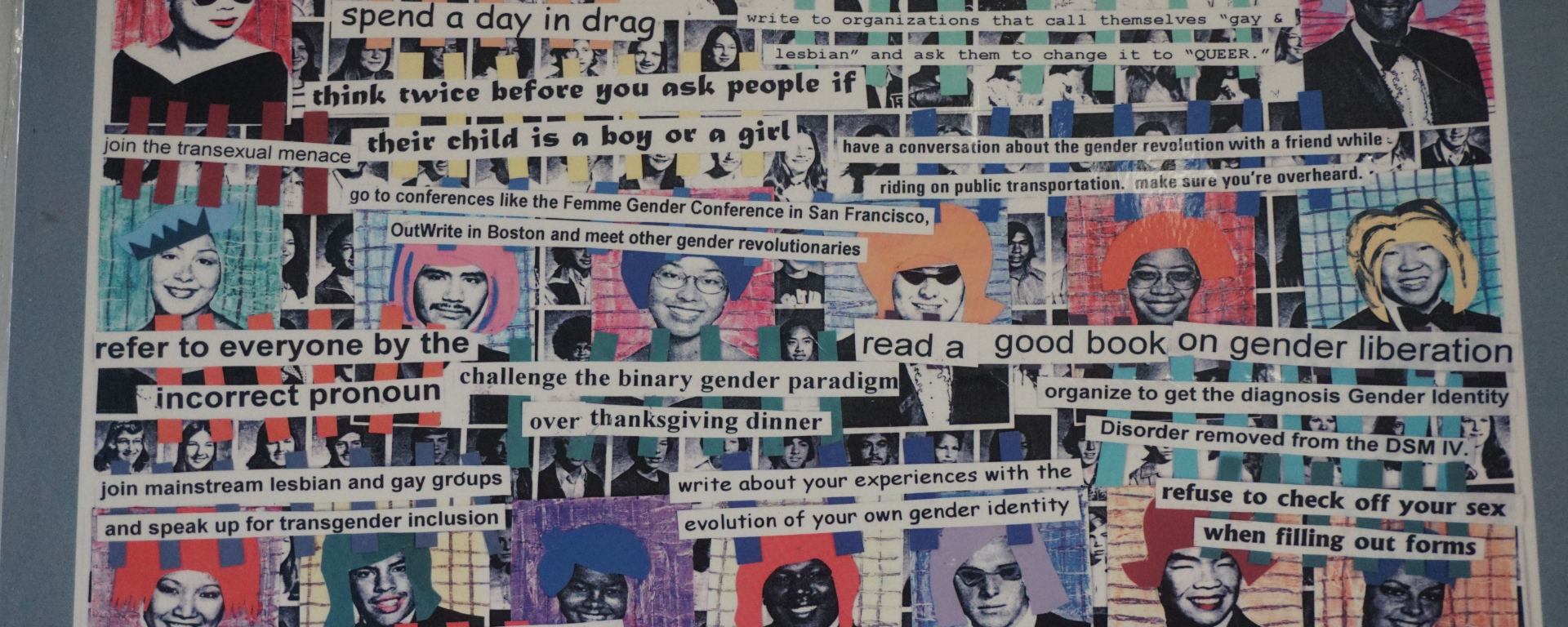

The temporary space the organization calls home in the basement of the Wellington Avenue United Church of Christ has many rooms, each with multiple purposes. Bright flyers advertising everything from drop-in needs to safe sex practices plaster the bulletin boards.

Services at the center include drop-in needs, disease testing, hormone treatment, housing placement for homeless youth, and resources for those who have been victims of physical, emotional, and institutional violence.

Maley said that violence against the LGBTQ community can often go under the radar. It is not always presented in overt forms, such as the shootings this past summer at Pulse, an Orlando nightclub. Violent acts can include everything from micro-aggressions and hate speech to institutions denying access to needs based on a person’s appearance or culture.

“I learned one of the biggest ways to make change is through structural change,” Maley said, sitting in the room that doubles as a meeting room and testing room.

Maley has always been a soft-hearted rabble-rouser interested in social justice. This led her to study anthropology and sociology at Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Georgia from 2006 to 2010. It was there that she studied the anthropology of public health, which taught her how structural inequality can lead to poor public health outcomes.

She continued her education at the University of Chicago, earning her masters in public health in 2012.

As a student, Maley volunteered 10 hours a week in a research position at the center. She then became the Youth Sexually Transmitted Infection Prevention Manager, and after working there for three years, she became the director of the entire center. Her rise through the ranks only encourages her passion for LGBTQ youth.

Kylon Hooks, the program manager for drop-in services, said Maley employs a radical management style and treats staff with the same care that is given to young people.

“She is absolutely passionate that young LGBTQ folks have the highest level of care provided to them through the services we offer,” Hooks said.

Maley prides herself on being the kind of director who knows how to do every job at the center. Even in her new administrative role, Hooks explained, “young people have direct access to her, so she doesn’t feel so removed from processes.”

When troubled clients bring violence into the center, the staff focuses on restorative justice methods rather than punishment.

“We know that you’re a person and you are worthy. Period,” Maley said.

A young trans woman she refers to as “Beyonce” was starting fights within the center. The staff recognized that the center was perhaps one of her only resources, and instead of denying her access, they met with her individually to assess her needs and how to meet them. Now, Beyonce has a job and a stable place to live, and she de-escalates fights within the center herself.

Jessi Peters, a junior at Columbia College Chicago, identifies as queer and lesbian and went to the center for STI testing. She lives on the South Side, where access to resources for LGBTQ youth is limited.

“It was very helpful to have a space when you’re young and black in the LGBTQIA community,” Peters said.

She felt privileged for the opportunity to go to places like the Broadway Youth Center where she doesn’t “have to choose and compartmentalize” different parts of her identity.

However, Peters said the center’s northern location in Lakeview makes access to its resources difficult. She wants to open her own center for LGBTQ youth on the South Side.

The center is a place “where people can be their whole selves and figure it all out a piece at a time,” Peters explained. “But we need more. It’s not enough, but it’s a start.”

Maley said the hardest part of her job is seeing young people do everything within their power, yet remaining unable to make real change in a system that fails them.

“I have a lot of guilt doing this job,” she said. “We can’t give people what they need because of our own boundaries and limitations.”

Maley said one solution to this is increased community involvement and awareness.

The center does cultural competency training with service providers and LGBTQ 101 on high school and college campuses. It is also present in neighborhood community meetings and aims to draw attention to internalized racism.

“The exciting thing is that people are becoming creative about ways we can create safety without calling someone who has a gun,” Maley said.

Maley said the center is “a magic place” that she loves helping to create. It aims to undo stigmas and creates an affirming space in which all bodies are beautiful and worthy.

Her clients inspire her through “the radical act of being themselves,” she said. “These kids inspire me in their bravery and resilience.”